We are constantly predicting the future.

We plan our road trips around avoiding traffic. We run conversations in our heads before they happen. We bet on sports or cards or celebrity deaths. We coerce two of our single friends into coming to the same party because we know for sure they'll hit it off.

Interestingly enough, we're pretty good at it. We're experts at examining the facts of the past, comparing it to the present situation, and drawing a line of trajectory through those two points and into the future to see where we'll end up if we stay on the current path. We might not get the specifics of the outcome exactly right, but things often end up in the general vicinity of our prediction.

We're so good at predicting the future that we can plot the course of several futures in our minds in order to set the most beneficial course of action for the present. Should we stay on course or make some choices that adjust the angle of our trajectory in order to land where we want to land? How much should we adjust and in what direction?

Here's a simple chart to demonstrate. If we make adjustment A1, A2 will happen. If we do nothing, B2 will happen. If we make adjustment C1, C2 will happen. We prefer the outcome C2, so we will make adjustment C1.

We do this every time we make a decision.

The best thing we can do for our improv is learn how to stop.

In Thinking Backwards for Good Reason we examined how improv operates differently than real life, which means we have to approach it differently.

At the very top of a scene there is only the present. The first move creates the dot.

At this point there is no shared past. We haven't discovered it yet. Because of this, there is no trajectory that can be traced into the future. A dot alone is not a line.

If the first move creates the dot, the reaction to that move defines the angle, setting the path for the rest of the scene. Now we have our trajectory.

This is great if we are being fully present and went into the scene with zero expectations, but we can get into some trouble if we tried to predict the future.

This often happens when we initiate with a preloaded line. When we have time to dwell on the scene before it starts we can't help but try to prepare for whatever might come next. We begin to invent a past, making assumptions about location and relationship and character that fit our initiation. These assumptions turn into projections of the future and expectations of behavior from our scene partner. "I'll initiate with this line, then they'll react this way, then I'll do this..." etc etc.

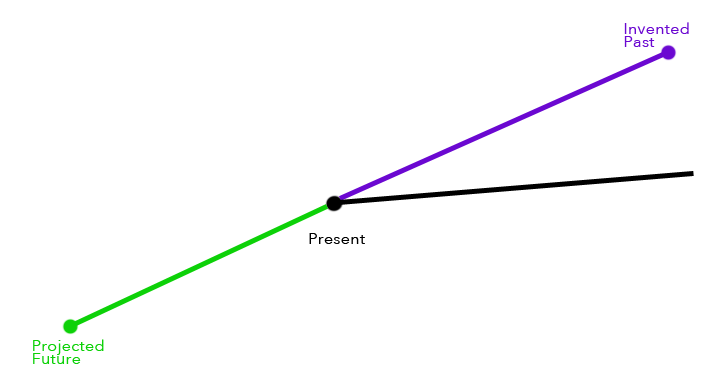

When we finally do initiate and our scene partner responds, we often end up with something like this:

In this instance our scene partner did exactly the right thing - they reacted to our initiation and set the angle of the scene. The problem is their reaction is a massive left turn away from our predicted trajectory. We were trying to get a head start on the scene and their move is so disparate from that plan that it throws us for a loop.

At this point it's very common to have the urge to reconfirm our intentions. We might feel that our scene partner didn't do what they were supposed to. They must have misinterpreted what we needed them to do. Maybe they weren't listening. But here's the thing -

Intention doesn't matter.

The invented past and projected future we constructed in our heads before the scene began isn't real. None of it. Once we initiate, our scene partner will take our line based on how they receive it and react accordingly. That's the reality.

For example, let's say we have an idea for a scene where notorious nice guy Mister Rogers is very mean when he's not on television. We decide that the best way to initiate is with the line "Wow Mister Rogers, I never expected you to be such a jerk in real life." We figure that gives our scene partner plenty of information for who they are (Mister Rogers) and how to act (like a jerk). In creating this initiation, we've also both invented a past (Mister Rogers just said something mean to us) and projected a future (Mister Rogers will keep saying mean things and we will keep being shocked and hurt).

But let's say we initiate and our scene partner responds with "I'm sorry...it's just that ever since Hammerstein died my musicals have been bombing. I'm so frustrated and lonely." For us this is a massively unexpected left turn. Despite what we thought was a clear initiation, our scene partner is both not who we expected (Richard Rodgers instead of Fred Rogers) and not behaving as we intended (apologizing and becoming vulnerable instead of acting like a jerk).

The easiest thing we can do in this moment (and the best thing for the scene) is drop our intentions completely. We might feel that since we put mental energy into our initiation and the expected context around it that dropping all of that pre-planned meaning would be a waste of a good idea. We might want to use some of the details from our original premise if we see windows to fit them in. But doing that is an act of friction. In order to make that tight left turn from our invented past into the current direction of the scene we have to slow way down so we don't skid off the road. It's so much easier to simply drop the past we invented and never have to make the turn in the first place.

Being fully present and not planning ahead allows us to be ready for any angle our scene partner defines by their reaction to our initiation. By having no expectations we never have to adjust our momentum and scramble to recover.

Thanks Bruce Lee

Locking ourselves to our intentions serves to act as if our imagined past and projected future are the correct path. We might feel that our scene partner wasn't listening or that they misunderstood what we needed them to do. We might attempt to course-correct - hinting that their reaction was misguided by saying things like "you usually don't act like this" or "are you sure that's what you want?" At best this becomes a disagreement about the reality of the world and the characters we're building together. At worst it turns into an attempt to control our scene partner's behavior.

We might try to ignore their idea for the direction of the scene and double down on ours ("Musicals? Mister Rogers, you're a children's television host!"). If they keep going in what we perceive to be the wrong direction, our hints might turn into demands like "You should really..." or "Stop acting like this..." If we really start to panic, verbal demands might escalate to physical force or threats of violence (I've seen performers pull guns on their scene partners to make them do what they wanted).

Try to recognize when your actions are less about supporting the scene and more about trying to control the decisions or behavior of your scene partners.

Attempting to control the behavior of others is an act of fear.

In our eyes their behavior is wrong, so we need to correct it to make it right. But their behavior isn't wrong, it simply violates our expectations. When our expectations are violated, we panic because our prediction for the future is suddenly wiped away. Our plan is suddenly obsolete. We don't know what happens next, which is a naturally uncomfortable and scary place to be.

Embrace not knowing.

It's not our scene partner's fault they didn't get what we were trying to set up. None of us are mind readers. It's our job to drop our predictions and adapt ourselves to their response. Committing to an imagined trajectory and trying to force the scene down a path it wasn't meant to go down will only cause it to stall out.

Make a dot, accept whichever direction your scene partner points it, and go.

Don't let yourself be guided by fear.

Stop trying to predict the future.